Every week I highlight three newsletters that are worth your time.1

If you find value in this project, do two things for me: (1) hit the Like button, and (2) share this with someone.

Most of what we do in Bulwark+ is only for our members, but this email will always be open to everyone. To get it each week, sign up for free here. (Just choose the free option at the bottom.)

1. Adam Tooze

This essay on war at the end of history is a banger:

War and history are intertwined. Entire conceptions of history are defined by what status one accords to war in one’s theory of change. War is certainly not the only way to punctuate history, but it is clearly one of the pacemakers. . . .

One of humanity’s recurring hopes has been that through history we might escape war. Since World War II Western Europe in particular has been invested in the idea of consigning war to the past. . . . The era of military history was thus consigned to an earlier developmental phase. . . .

From this point of view, if major powers did “still” engage in war - as many regrettably did - it was either a sign that they were regressing to an earlier stage of statecraft, under the malign influence of reactionary elites. Or the elites in question had fundamentally miscalculated, not grasping the real stakes, or the proper means with which to pursue their best interest. Or the war in question was simply not very important, less a historic turning point than an atavistic indulgence. “Wars of choice” are an occasion to show off the raw power of the state without facing serious resistance. . . .

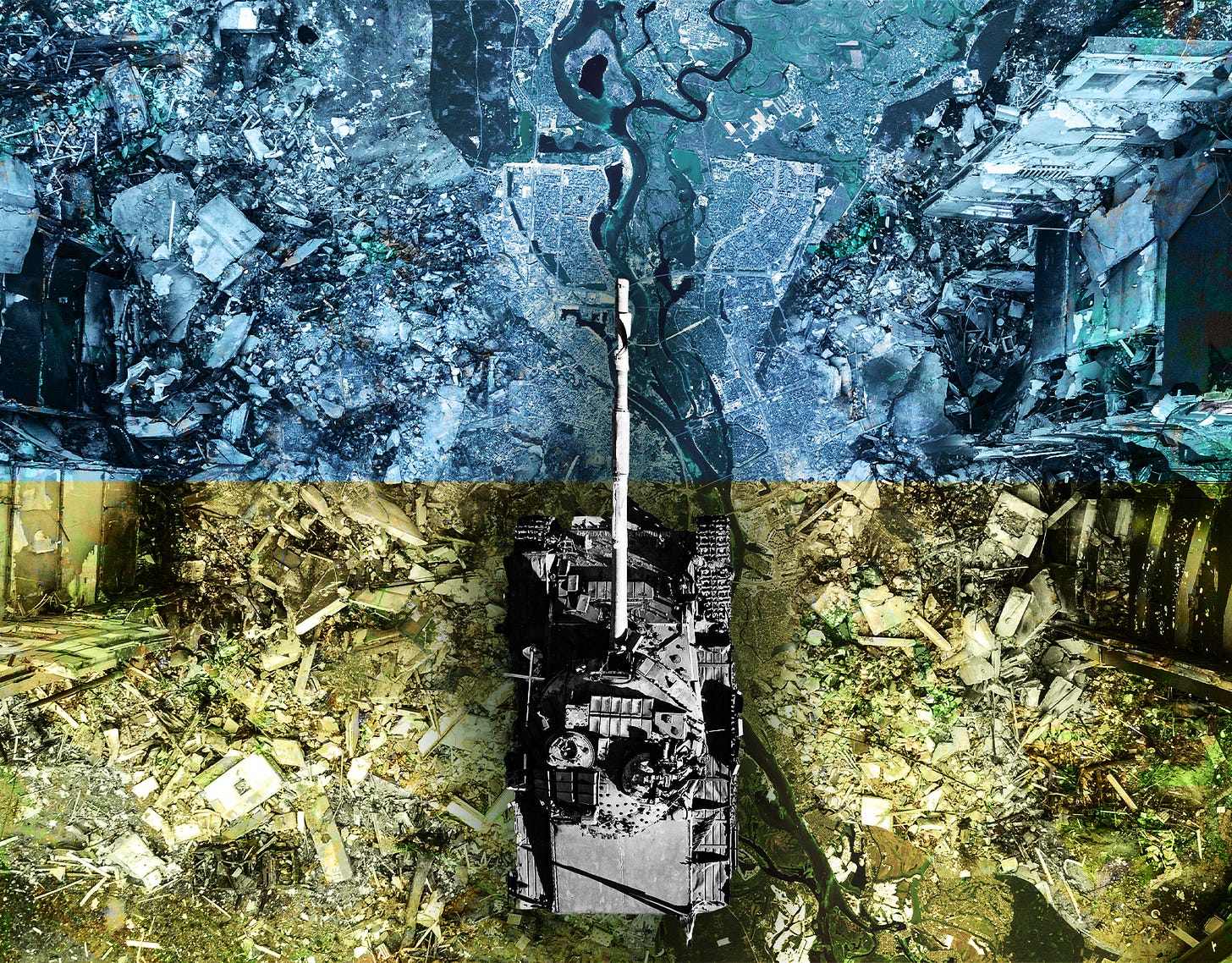

Russia’s assault on Ukraine is shocking, therefore, not only for its violence, but for the fact that it reopens the question of war as such and thus also the question of history . . .

[I]n the final chapter of The End of History, Francis Fukuyama had anticipated a strong-man figure who might want to overturn the end of history by force majeure. This figure would want to restart the struggles of the past, to restore meaning and humanity to existence, almost regardless of ideological content. It would be the struggle for status that mattered, per se. . . .

So if the Ukraine war marks a a break, to put the emphasis on Putin may be misguided. If the honor of rekindling history, of “returning us to the 19th century” belongs to anyone, it is not to Bunga-Putin. That honor belongs to the Ukrainians.

It is the Ukrainians, to the amazement and not inconsiderable embarrassment of the West, who are enacting a drama of national resistance unto death.

Read the whole thing and subscribe.

There’s a lot going on here, some of which I tentatively agree with. Some of which I’m even less certain about.

Because one of the keys is that outcomes matter. How we view this conflict will depend entirely on who wins, and how.

For instance, if the war had taken the path I had first expected—Russia invading, toppling the Ukrainian government, partitioning the country, and installing a puppet regime—then we’d learn one set of lessons.

If, on the other hand, Ukraine pushes Russian troops out of their country and the resulting chaos ends with the toppling of the Putin regime, then we will learn another.

And in between those poles are a wide range of outcomes. It matters who wins. And these outcomes are not predetermined.

2. Every

This essay about “The CEO of No” was incredibly helpful to me because 50 percent of my life’s struggle is about guarding my time. The piece by Andrew Wilkinson, the CEO of Tiny, about how he manages his time was like a series of lights flicking on in my brain:

I had the chance to get really up-close and personal with a lot of founders. I had a front-row seat for all of their successes and failures.

What did I see? Most of them were miserable. They weren’t optimizing for happiness. They weren’t enjoying their lives. They weren’t sleeping. Their marriages were suffering.

It really made me question whether I would be willing to sacrifice my home life — be a bad dad, get sick all the time, lose my marriage or my health — just to achieve something ‘huge’. . . .

What I do instead is try to structure my life around how to make myself happy, and how to make my family happy.

Now that I have enough to do that, I get to ask how I can make my employees happy, and make my community happy. That means continuing to grow the organization, because that lets us promote people and pay them more.

Ultimately, building more freedom means we can really build up a wall between ourselves and the things we don't like doing.

A lot of what Wilkinson does is on email (it=me) so a lot of his optimization strategies are around how to manage email, both as a technical matter (I’ve started using both Superhuman and Mailman2) and as a philosophical matter. Here’s Wilkinson:

When I’m dealing with emails, sometimes I just have to refuse people’s requests.

At first, I’d say yes to everything — meetings are really valuable when you’re starting off. But I reached a point where I was letting myself get scheduled on six to eight hours of phone calls a day. And when I looked at them, I couldn’t identify what the positive outcomes were — and more importantly, I didn’t enjoy doing it.

If I did everything like that, I would end up sacrificing my own life for other people. And that’s just not what I want to do, so I started to say no a lot.

But saying no in all of its forms — be it refusing a request, firing somebody, cancelling something, or dealing with sunk cost fallacy — is really, really hard. It’s emotionally burdensome.

So I try to be very deliberate about how I have those difficult conversations. If somebody makes an email request that I need to say no to, I have a wide variety of response templates in Superhuman that allow me to do it in a nice, polite way.

For example, if somebody emails looking for us to invest in their startup, I have a short, friendly response template email ready to go that explains that we don't really do venture investing. . . .

I have a bunch of these different ways to let someone down. For example, if I get a request from a business that's too small, it’s 'Sorry, your business isn't big enough'. Or from somebody wanting to pick my brain — ‘Thanks for thinking of me, I’m very flattered; can I offer some of my writing as an alternative?’.

There's actually a big library online of all the different ways to say no — they’re just gold. I’ve spent a lot of time evolving and dialing in these templates for my own use, and it’s been super useful.

I know—this is kind of rich coming from me, because I respond to like 90 percent of emails from people. Partly that’s because I view conversing with readers as part of the compact writers make with the audience. Partly it’s because I enjoy it. You would be shocked to know how many of the people who read these things have become pen pals, or even real-life friends.

But also: I’m coming to terms with the fact that I need to guard my time. So if I value being a correspondent with readers, it means that I need to say no to other things. For instance: I basically will not talk to people on the phone. I guard synchronous communication time like it’s Fort Knox.

And casual get togethers? Getting coffee or having lunch with a professional acquaintance? No chance. Zero.

Even meetings, we keep to a bare minimum at The Bulwark: We have a once-a-week team meeting with a kill switch set for 30 minutes.

My point in all of this is that everyone should be intentional about how they use their time and be clear-eyed about what’s important to them. And then willing to say no to the things that aren’t.

3. Rhapsody

So much JVL Life Hacking today! Joe Ragazzo tackles another issue that I struggle with:

Have you ever had a passion you pursued, but eventually it started to feel like “work”? Perhaps whatever you’re passionate about actually became your career, and for some reason, you lost interest in this passion. How does this happen? . . .

In this context, something you’re passionate about is something intrinsically rewarding, which means that the act of doing the thing is rewarding in and of itself. The incentive is built into the action. . . .

We all have passions that we pursue without anyone poking or prodding us. We might even make time to do these things. On the other hand, if we are tired or not in the mood, we simply will not do them. Whether or not you ever stop to contemplate this basic fact, cognitively, you are aware that you are in control and this feels good.

However, when some force compels you to do a thing at a certain time and in a certain way, there’s a chance you lose some of that autonomy.

In his 1968 work Personal Causation, Richard De Charms developed a concept he called “Perceived Locus of Causality,” which referred to the idea that individuals are more motivated to do something when they believe they are acting of their own volition. It speaks to the level of autonomy a person feels when they decide to act, and this is experienced on a spectrum ranging from totally autonomous to controlled. . . .

In many contexts, if our passions become too easy or too difficult—if we feel that we are no longer growing—we’d likely stop doing them altogether. Our intrinsic motivation would dry up. But sometimes we don’t have a choice, right? Perhaps our career is built on this passion and our means of making a living. Well, now we’re not doing it for the intrinsic benefit, we’re doing it for extrinsic reasons. We feel controlled and lacking in autonomy. We no longer derive a sense of competence from completing required tasks. Our passion has become “work.”

Good employers, good coaches, good organizations of any kind consider optimum challenges when they construct career paths and job descriptions. They know that the more you can harness and support someone’s intrinsic motivation by providing optimum challenges, the happier that person will be, which benefits everyone involved.

Read the whole thing and subscribe.

If you find this newsletter valuable, please hit the like button and share it with a friend. And if you want to get the Newsletter of Newsletters every week, sign up below. It’s free.

But if you’d like to get everything from Bulwark+ and be part of the conversation, too, you can do the paid version.

Except for the last couple weeks—I was sick. Sorry.

These two apps have absolutely changed my life. I’m getting about 2 hours back, every day. I cannot recommend them enough.

I couldn't agree more on that second point. I wish more people were conscious of their time. Spending time is spending life, understanding it to be the resource that it is. Understanding what you are spending your resources on and getting something out of them are the keys to lasting personal happiness -- and to making the most of what time you have with loved ones.

This is great. The founders commentary is so true. If you ruin everything personal, what’s the point !?